ASC 740 Income Tax Provision Rules for Controlled Foreign Corporations

Calculating the ASC 740 provision for income tax can be challenging enough for a U.S.-based corporation, but it can become even more complicated navigating how ASC 740 applies to foreign-source income. Below, we outline how income from a controlled foreign corporation is taxed in the U.S., including how to account for deferred tax assets and foreign tax credits.

How does the IRS define a controlled foreign corporation?

Controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) are entities that are directly or indirectly majority controlled by a U.S.-based parent company but organized under foreign law. For U.S. income tax purposes, they are treated as corporations. CFCs typically do not have U.S. operations.

How is the ASC 740 provision calculated for taxable income from controlled foreign corporations?

A CFC must calculate a separate current, deferred, and noncurrent ASC 740 income tax provision for each jurisdiction in which it is subject to tax.

ASC 740 presumes that the earnings of a subsidiary will ultimately be repatriated to its parent. Therefore, any deferred taxes that would arise from the repatriation are accounted for in the period in which the earnings occur rather than the period in which the earnings are repatriated.

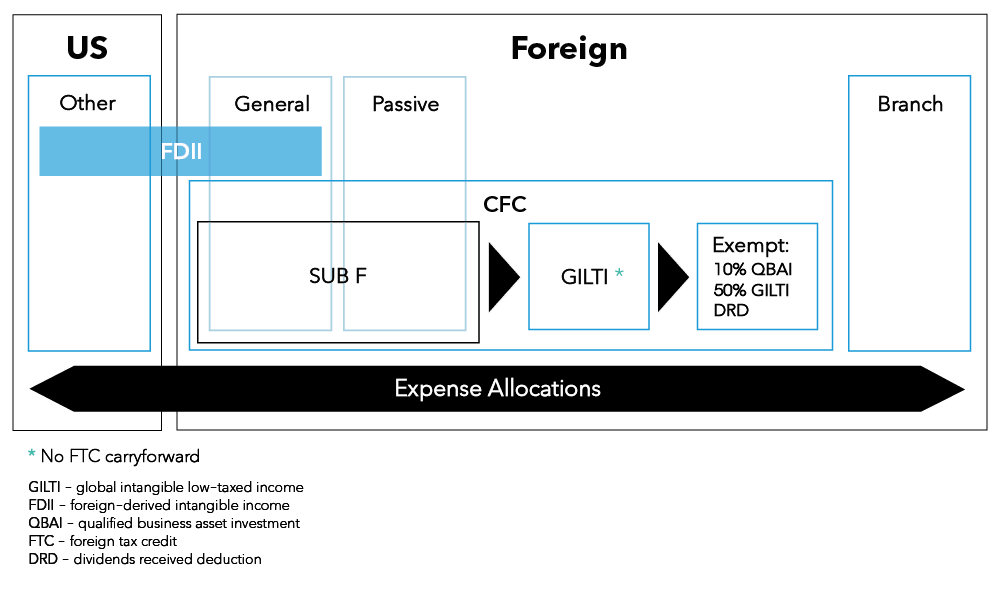

Accordingly, practitioners should calculate the U.S. tax effects associated with the repatriation of a CFC’s earnings based on the expected manner of repatriation – often a dividend. The dividends received deduction (DRD) under Sec. 245A offsets the U.S. impact of any foreign dividends from CFCs. This DRD is sometimes referred to as the “exempt basket.” The provision calculation should include any foreign tax credit and foreign exchange impacts that would be triggered upon repatriation.

Accounting for deferred tax assets and liabilities from controlled foreign corporation earnings

A deferred tax liability is recorded to the extent that the repatriation of earnings would result in additional income tax to the U.S. parent of the CFC. That deferred tax liability needs to consider the following components:

- Withholding tax imposed on the dividend

- State tax associated with the dividend

- Section 986 foreign exchange gain or loss

A deferred tax asset associated with unrepatriated earnings is recognized only to the extent it is expected to reverse in the foreseeable future. In practice, the foreseeable future is typically understood to be less than one year from the balance sheet date.

Indefinite reversal exception to recognizing deferred tax liabilities

ASC 740 allows a specific exception to the recognition of a deferred tax liability on the outside basis difference/U.S. tax consequences of repatriating the historic earnings of a foreign corporation or foreign corporate joint venture if the earnings are expected to be permanently reinvested outside of the U.S. To satisfy the indefinite reversal criteria, a company must have a plan to reinvest its foreign earnings.

A company may make distributions out of current year earnings without contradicting an assertion that it is permanently reinvested with respect to historic earnings.

Though the indefinite reversal criteria are most often applied to the earnings of a CFC owned by a U.S. parent, the permanent reinvestment assertion is available to any corporation and corporate joint venture that would constitute a foreign entity from the perspective of its parent.

The repatriation of historic earnings from a foreign entity that has asserted the indefinite reversal criteria does not constitute positive evidence when considering the need for a valuation allowance against a deferred tax liability.

Sources of controlled foreign corporation taxable income and related foreign tax credits

The creation of the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) regimes expanded the range of situations in which U.S. income tax may be imposed on some or all earnings from a U.S. corporation’s CFC’s operations.

Accumulated earnings and profits

A CFC must track its annual earnings and profits, known as accumulated E&P. E&P represents the economic profit of the CFC and its ability to pay dividends. E&P is similar in concept to retained earnings but subject to certain adjustments.

A CFC’s accumulated E&P is tracked in the company’s functional currency. Dividends are deemed to arise from current year E&P and then from historic E&P. To the extent that a CFC doesn’t have E&P, dividends are treated as a nontaxable return of capital.

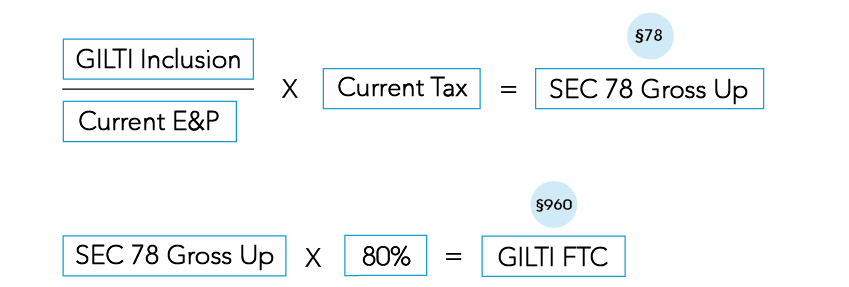

Under U.S. tax law, the Section 78 gross-up is the mechanism for addressing the inherent tax included in E&P.

U.S. corporations that satisfy ownership and other requirements are permitted to take an indirect foreign tax credit for taxes paid on the profits from which dividends were distributed. Under IRC Sec. 78, these taxes are “deemed paid” by the U.S. corporations. Consequently, the dividend income is “grossed up” by the amount of taxes deemed paid on the income from which the dividend was paid.

The calculation of the Sec. 78 gross-up considers only current year E&P and foreign taxes. A separate Sec. 78 gross-up is calculated for each deemed dividend and included in the appropriate foreign-source income basket and foreign tax credit calculation.

Subpart F income

Since the Revenue Act of 1962, which refined the definition of a CFC, Subpart F of the Tax Code requires U.S. shareholders of a CFC to include Subpart F income – made up mainly of passive income – in its current-year taxable income regardless of whether the CFC distributes that income to the shareholder in the current year.

Subpart F provides for several exceptions to the general rule of deferral of current taxation on the income of a CFC when calculating the ASC 740 income tax provision.

Subpart F income is considered a deemed taxable dividend from the CFC to its U.S. parent, followed by a subsequent capital contribution back to the CFC.

U.S. tax law allows taxpayers to claim deemed paid or indirect foreign tax credits based on the proportion of taxes paid by a CFC on its distributed (deemed or otherwise) earning and profits.

A dividend or deemed dividend is generally included in the appropriate foreign-source income basket based on whether it arose from trade or business activity versus passive activity.

Two common types of Subpart F income are foreign personal holding company income and foreign base sales company income. Determining the appropriate amount of Subpart F income in a given year involves analyzing the numerous exceptions to and additional complexities of the general rules.

Foreign personal holding company income

Generally, a CFC’s interest income, dividends, royalties, and gains on sale of property not used in a trade or business are considered Subpart F foreign personal holding company income (FPHCI). FPHCI is taxable to the U.S. shareholders of the foreign corporation at the time it is earned.

FPHCI is generally passive basket foreign-source income for the purposes of calculating the foreign tax credit.

Foreign base sales company income

Foreign base company sales income (FBSCI) is income derived from either buying products from a related party and selling them or buying products and selling them to a related party, where the products are both made and sold outside the CFC’s country of incorporation. FBSCI is taxable to the U.S. shareholders of the foreign corporation when it is earned.

FBSCI is typically general base foreign-source income for the purposes of calculating the foreign tax credit.

GILTI inclusion calculation

The GILTI regime taxes U.S. shareholders on certain CFC income, like Subpart F.

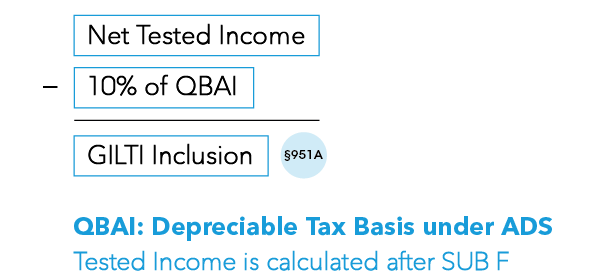

In the context of GILTI, the term “intangible” is a misnomer in that it doesn’t relate to income from actual identified intangibles. Instead, it is a deemed amount above a 10% return on fixed assets.

The GILTI inclusion is calculated based on the following equation:

For each CFC, net tested income is the income for the year less any Subpart F or other designated items. In other words, Subpart F is always accounted for prior to GILTI.

The qualified business asset investment (QBAI) is equal to the CFC’s depreciable tax basis under the alternative depreciation system (ADS).

The GILTI calculation is complex and involves an aggregate analysis at the U.S. shareholder level and then an allocation of those outcomes back to the related CFCs.

GILTI foreign tax credits

A separate Sec. 78 gross-up is calculated for GILTI. Though the GILTI basket has foreign tax credits associated with it, there are two significant differences between GILTI foreign tax credits and foreign tax credits in the other foreign-source income baskets:

- The allowable foreign tax credit on GILTI income is limited to 80% of the Sec. 78 gross-up.

- A foreign tax credit carryforward isn’t allowed for GILTI income.

Since expenses are allocated against GILTI, a company will incur a current tax payable associated with GILTI despite the allowance of foreign tax credits and Sec. 250 GILTI deduction.

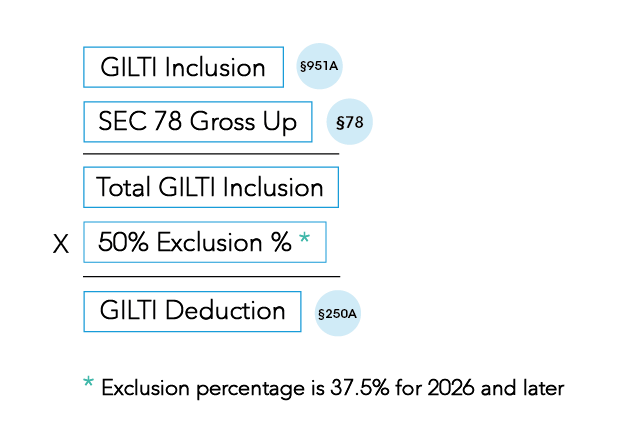

Sec. 250(a) deductions

The deduction under Sec. 250 has the impact of limiting the adverse effects of GILTI. For tax years 2018-2025, there is a 50% deduction for the GILTI inclusion and the related Sec. 78 gross-up. For tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, that deduction will be reduced to 37.5%.

Sec. 250(a) also addresses foreign-derived intangible income (FDII), which is a U.S. corporation’s income deemed to be derived from the sale of goods, provision of services, or license of intellectual property for non-U.S. use.

Sec. 250 allows a domestic corporation to deduct 37.5% of its FDII for the 2018-2025 tax years. For tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025, the deduction will be reduced to 21.875%.

The FDII deduction calculation is complex. Deemed intangible income (DII) is a U.S. corporation’s net income reduced by a fixed 10% return on QBAI, like the GILTI calculation. DII is multiplied by a foreign-derived ratio, which represents the portion of the DII related to exports for use outside of the U.S.

The deduction is subject to limitations related to GILTI and taxable income under Sec. 250(a).