Detangling State Tax Conformity

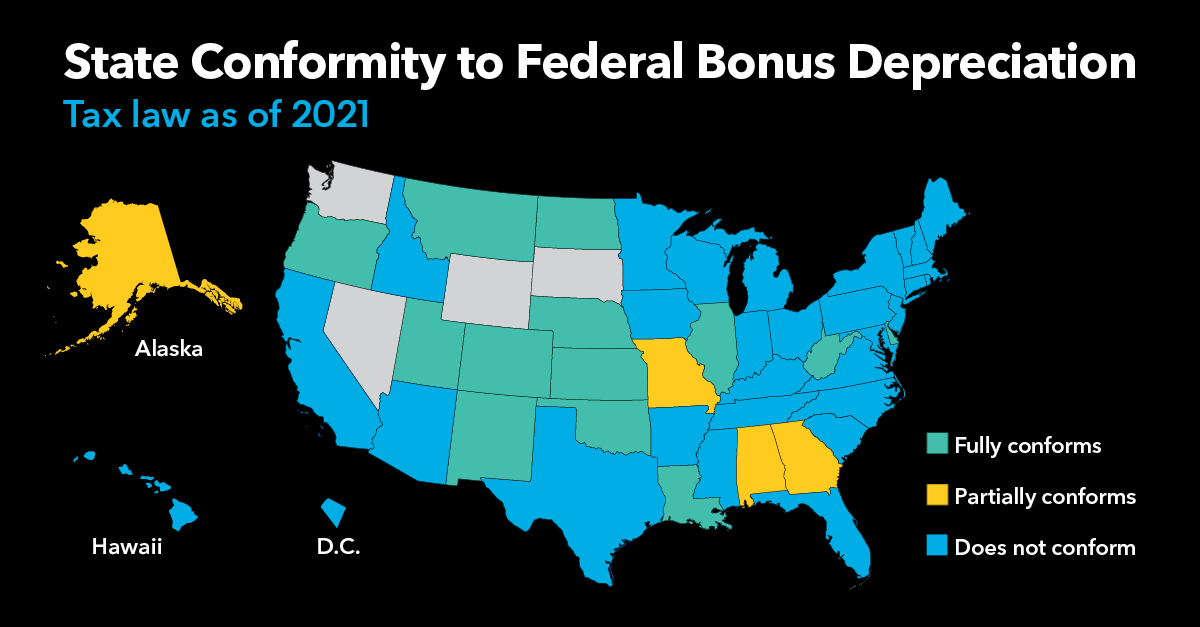

Calculating state depreciation has long been a source of frustration and stress, with tax accountants going cross-eyed staring at complicated spreadsheets while under the looming threat of audits or fines. Since bonus depreciation was first enacted by Congress in 2002, many states have opted not to follow the provision and have required taxpayers to add back amounts deducted for bonus depreciation.

With the passage of federal legislation, states often make a flurry of updates to their own laws to either comply with federal standards of depreciation or decouple from the new standards to amplify their own tax revenue. In the area of fixed assets, state nonconformity isn’t as simple as bonus or no-bonus, and practitioners need to be aware of the various (and sometimes downright strange) treatments of fixed assets depreciation across the 50 states.

Of course, things would be much easier if all 50 states and the federal government followed the same tax standard when it comes to depreciation rules, but when has tax accounting ever been easy? To help navigate this tangled web of state conformity, here are three things taxpayers can start doing today.

1. Stay on top of state legislative changes.

States will change their conformity depending on a variety of factors, including the economic situation and the political environment – or in response to the changes in businesses or industries that are in the state. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic and 2021 presidential transition have sparked even more activity in this area.

States are changing their laws all the time, and it’s not always national news. To ensure compliance, keeping track of the changes to each state’s tax laws is a must. When looking at state conformity changes, keep in mind there are three patterns:

- static conformity, also known as fixed-date conformity

- rolling conformity; and

- partial, also known as selective, conformity.

“You need to make sure that you watch out for particular state conformity issues when computing, not just your depreciation, but all of your state taxable income,” says Ryan Sheehan, senior product lead for Bloomberg Tax Fixed Assets and former CPA at KPMG.

Static conformity means that the state conforms to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as of a certain date, and legislation is required to change that conformity date. This means that when the 2020 federal legislation passed, these states were automatically not conforming to any of the new standards, and they had to enact legislation to make any desired changes.

Minnesota is an example of a static conformity state that is conforming to the IRC, as amended through December 31, 2018. Since that date, Congress has enacted legislation, most notably the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) and 2020 Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act (TCDT). These acts include changes affecting businesses for tax year 2020.

For example, Section 2307 of the CARES Act fixed the “retail glitch” related to qualified improvement property (QIP). Because Minnesota has not adopted these federal changes, depreciation adjustments are required to correctly determine Minnesota taxable income.

For states that conform to the IRC automatically on a rolling basis, legislation is also required if the state chooses to decouple from specific provisions. This creates a risk for taxpayers in the state, as they are essentially required to file their taxes without knowing for certain if the state plans to opt out.

Partial or selective conformity means that states can pick and choose which provisions they conform to or decouple from. For example, they might be able to opt out of following bonus depreciation under Section 168(k) while still allowing first year expensing under Section 179.

“It’s important to note that conformity is not something that’s uniform,” Sheehan says.

Pennsylvania and Illinois are examples of states that have made changes to their conformity over the years. Both states previously allowed bonus depreciation but required a formulaic modification to adjust the timing of the deduction. However, after the passage of the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA), Illinois allows taxpayers to take 100% bonus depreciation, whereas Pennsylvania does not.

Keeping a close eye on legislative activity is critical to ensure the most up-to-date standards are used when calculating for state purposes. Setting up email alerts for when a state tax webpage is updated is one option. Another way is to subscribe to tax research platforms. Resources such as Bloomberg Tax Research offer updates as well as analysis from leading practitioners that help users plan and comply with confidence.

2. Consider the implications of decoupling.

The most obvious impact of decoupling is that it results in different depreciation expense between federal and state. While that sounds simple enough, it can create complications from a process standpoint.

For instance, decoupling creates a modification that taxpayers will have to calculate and report on their state tax returns. Given that states have different forms, taxpayers will need to figure out how to transform their calculations into an acceptable format specified by each jurisdiction.

Additionally, the impact of decoupling on an asset’s adjusted basis leads to differences in gain or loss when that asset is disposed – whether it is through a complex sale, like-kind exchange, or simple retirement.

“One thing that people don’t often think of when it comes to differences in gains or losses is how that impacts the apportionment factor for states,” Sheehan says. “Some states will actually include a gain or loss in the denominator of a sales factor or in the numerator of a sales factor. So that’s something that can be impactful.”

Partially conforming states add another layer of complexity. With the multiyear tracking of bonus and section 179 expense, taxpayers can’t just focus on one year when they run their depreciation reports. Some states, such as North Carolina and Florida, require tracking of additions and subtractions over multiple years, which can be time-consuming and error-prone, particularly if a taxpayer does not have software that calculates the modifications automatically.

3. Choose a powerful software solution.

Tax software can not only simplify the fixed assets management life cycle but also save time and money with automated fixed assets tracking, processes, and calculations.

Below are some considerations when choosing a software that handles state tax depreciation:

- The software should enable users to set up different books to calculate state depreciation. For simple non-conforming states, a book can operate the same way as for federal taxes, but without taking bonus. This is generally a strong approach, however, be conscious that issues could arise if a state has varying conformity over the years or exceptions to the rules depending on the asset type.

- The software should have a system in place to track year-over-year differences generated from the net effect of bonus addition and subtraction modifications.

- And finally, the software should make it easy to reconcile the adjusted basis of each asset for a given period. For example, if any assets are disposed, the software should automatically determine gain and loss and know whether that state allows the taxpayer to deduct any unrecovered bonus depreciation in the year of disposal.

“We see a lot of our clients doing this on an Excel spreadsheet but having it in [tax] software is the best way to go,” Sheehan advises.

State Depreciation, a one-of-a-kind software feature in Bloomberg Tax Fixed Assets, handles all of these considerations and untangles the complexities of state depreciation by moving past simple “no-bonus calculations” into complete, accurate, and quick calculations that help save time and minimize risk.

With the state depreciation feature, stay up to date on state laws, seamlessly account for tax and financial depreciation differences, and, best of all, never have to manually calculate state depreciation on a spreadsheet again.